“Childhood cancer survivors may be cancer free but we really aren’t free from cancer.”

By Maggie Rogers, MPH, End Well ePatient

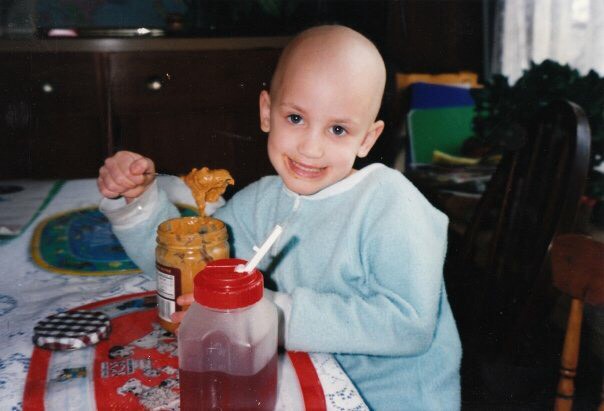

When I was a kid I had cancer. A malignant tumor the size of a softball caused my kidney to rupture while I was playing with my dad. It took two different hospitals to figure out that I had stage III Wilm’s tumor, a pediatric kidney cancer affecting roughly 500 kids per year in the United States. I was a given a favorable prognosis, and after a year and a half of surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and being made fun of in kindergarten for being bald, I didn’t have cancer anymore.

As a teenager, I was active in the cancer community. I organized large-scale fundraisers, attended cancer events, and spoke about my experience in front of crowds of hundreds. I went to my follow-up appointments with my oncologist and care team. I was proud of what I had lived through. I wrote about cancer for my college essay. To me, survivorship was laps on a track and memories of traumas-past.

In my early twenties, my life as an inspirational/brave/hero/[insert other cancer survivor compliment here] got turned on its head. In the course of a few years, I ended up with multiple skin cancers that required specialized surgeries, my health insurance sent me home from study abroad after I started peeing blood, I had to have surgery to remove my ureter, I went into premature menopause, started being followed by a million specialists annually, and ultimately stopped talking about my cancer debacle. I was angry; this was not what cancer survivorship was supposed to be.

It’s during this time that I started researching and reading the published literature on late effects of childhood cancer treatments. Health conditions that can pop up decades after treatment ends. It’s not pretty. As many as two-thirds of us will end up with at least one late effect of treatment and as many as one-fourth will experience a serious or life-threatening late effect. We get cancer again, like breast, lung, and thyroid. We suffer from heart conditions and organ failure. We have PTSD and other psychological effects. We can’t have children. And if we can, we probably can’t carry them. We age faster and we die sooner. Our life expectancy is 30% less than the general population. We suffer and sometimes die from the late effects of a treatment that once saved our lives. We may be cancer free but we really aren’t free from cancer. It can happen at any time and without warning. Our bodies are ticking time bombs.

When the success of a cancer survivor is measured in “years cancer free,” it’s difficult to come to terms with being a failure. As I said, this wasn’t what cancer survivorship was supposed to be. But this is exactly what cancer survivorship is secretly like for many of us; our cancer survivorship kills us or comes back to haunt us. And the health system is ultimately failing us; Physicians don’t know what to do with us and medical students don’t learn about us.

I started thinking more about how we die. So much of how we die is tied up in our complicated health care system, which somewhere along the way stopped being about the people it’s supposed to be helping. I started thinking about how we endure serious illness and how we maintain a quality of life in the face of adversity. And more importantly, I started thinking about how we live. So much about ending well is, in fact, about living well.

There is no magical answer. This experience has been a reminder that, even though it might not seem like it and even if we don’t see any immediate effects, the actions we take now, the stories we tell now, the lives we live, the small changes that happen now can have long-lasting impacts down the road — on ourselves and the healthcare system. A ripple effect that eventually hits shortline. Studies on late effects have led to changes in treatment plans and improved quality of life for the next generation of pediatric cancer survivors. And that’s what I hope for by the sharing this story. I’m not expecting an immediate response to our cry, just maybe some late effects.

Maggie Rogers is a stage III cancer survivor and public health researcher. Propelled by her own experiences as a patient, she dedicates her time to improving the quality of life for other patients and cancer survivors. Maggie is the Director of Research at the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) in NYC.