Death is a lot like sex. It’s a taboo subject that makes us squeamish, so we avoid it. And like sex, if you aren’t prepared for the end of life, it can go very badly. — Jessica Zitter, MD, MPH

Death is a part of life that we don’t want to acknowledge. But it’s happening around us all of the time. And here’s something interesting:

More than three decades of palliative care research, and probably even more, have shown us clearly that when people know more about the end of life, they live and they die better.

And yet, in these modern times, the majority of us know very little about death. Whatever we do know we learn in snippets from TV shows that are completely unrealistic.

Why Are We Bad at Dealing with Death?

It wasn’t always this way.

For the majority of human history, people knew how to manage their dying loved ones. When they were sick and dying, they were cared for in the home. And after they died, they were laid out in the parlor.

Death was expected, it was accepted, it was prepared for.

But things really changed in the 1930s. At that time, two professors of industrial hygiene at Harvard School of Public Health, using the motor of a vacuum cleaner, created a machine that went on to save thousands, many thousands of young people and older people from death from polio.

It was known as the “iron lung”. Today, in its new iteration, it’s known as the modern mechanical ventilator, and is found in intensive care units around the world.

Around the same time as the iron lung was being developed, on the battlefields of World War 2 and Korea, doctors were learning how to measure pressure inside of vessels using catheters, how to do resuscitations with fluids and volume and plasma, and how to save many thousands of soldiers from death from hemorrhage and shock and infection; people who would certainly have died on the battlefields.

And so people began to be saved by technology. And it felt like a miracle. And many began to believe in these machines: if they could save young children, soldiers, maybe they could save us all. Maybe they could save the old, the ill. Maybe they could save the dying.

The End-of-Life Conveyor Belt

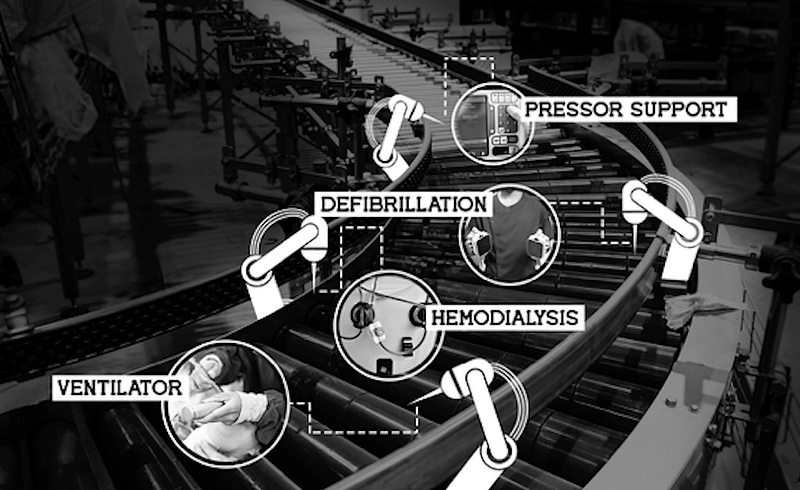

The result is something called the end-of-life conveyor belt, which is seen everyday in the intensive care unit.

This is where patients who are truly approaching the end of life get plugged into a series of machines and submitted to a series of technologies and treatments and protocols that compensate for all of their organs as they begin to fail.

And the final stop is ventilator facilities, where people are surgically connected to these machines.

They frequently have their arms tied down, and they are frequently in pain, confused, and probably not aware of what they were submitting themselves to or signing up for.

This is a rising public health crisis of extraordinary proportion. And it’s not what people want.

Denying this reality does not solve the problem. The antidote is education. One solution to denying death is death education that enables people to make decisions based on knowledge, and not fear or fantasy.

“Over the last century, we have forgotten how to die. And for that, we’re suffering greatly. And so death ed is our attempt to bring some age-old wisdom back into the classroom so the next generation can live their lives fully, all the way to the end.” — Jessica N. Zitter, MD, MPH

So Are We Currently Teaching Death Ed?

No. The reality is death education isn’t being taught. Only one program existed in upstate New York some 25 years ago.

So how do you create a death education curriculum for high school students? Where do you start?

What if talking about death deeply upsets students? What if people get angry? What if someone gets so traumatized they run out of the room screaming? Could discussing death openly incite depression in kids?

The “Death Ed” Experiment

Drs. Gross and Zitter approached two high schools in the Bay area and asked if they would be willing to pilot a death education program with their students. Both schools said yes.

To prepare, they then did what any science educator would do: they created an advisory panel to tell them how to do this. That advisory panel was made up of their teenage daughters and their friends.

They asked, “how do we make sure what we’re going to teach is actually successful?” They suggested three, straightforward things:

1. Use candy wherever possible

2. Remember that movies never hurt

3. Be as interactive as possible

Part 1: Death & Candy

Day one started with an exercise that involved candy and an interactive activity.

Each student was given colored candy, and told to put the appropriate candy in the jar if the following conditions applied to them.

1. Red candy: loss of a parent or sibling.

2. Orange candy: loss of a grandparent, an aunt, uncle, or cousin.

3. Yellow candy: loss of a teacher, a counselor, or coach.

4. Green candy: loss of a pet.

5. Purple candy: loss of an admired public icon.

Once every student added their appropriate candies, they were asked what they saw. In every single classroom, the students noticed two things.

First, there were more candies in the jar than there were people in the room. And second, every single color was in the jar. They realized death had already touched them, and was likely to touch them again.

On that first day, the context for the importance of learning about death was created. The next step was to uncover what the students knew about death.

Part 2: Death & Movies

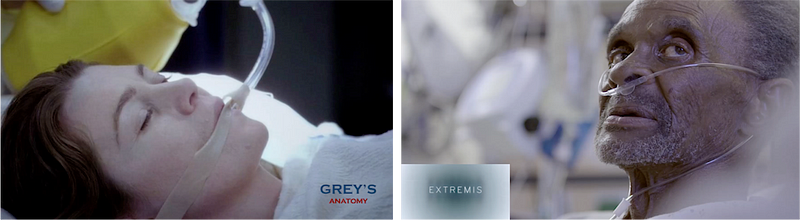

On that first day, students were then shown two videos. The first was from something they were eagerly familiar with; one of their favorite TV programs, Grey’s Anatomy.

In this particular episode, the heroine of the show actually dies. As she dies, all of the heroics of the medical conveyor belt come out in all their magical glory and resurrect her. And she comes back to life.

By the end of the episode, she’s able to sit up by herself in her hospital room, look at Dr. McDreamy in the corner who’s smiling, and they coyly say, “Hey.”

The students were captivated. They loved it. And when asked about what they saw, they said, “Oh no, we know that’s not real. We know that’s made up.”

So what is real? They couldn’t tell us.

So we offered a different clip, this one taken from the documentary Extremis, which features Jessica Zitter in her hospital intensive care unit. The documentary follows patients, doctors, and families who are facing very real life-threatening illnesses, most of whom are either not in a position to answer for themselves what matters most, or their families have never talked about it, and so don’t know how to answer on their behalf.

In this viewing, the students were equally as enraptured with the video. But instead of laughing, they cried. When approached after to say, “Are you okay? Is it okay you saw that?” they said yes and that the tears were important. And in fact, the fact that they’re crying indicates we should be talking about it.

“In the days between class one and class two, we were terrified because we realized we had left these students in a place of caring about talking about death, but we hadn’t taught them how to. And we were worried about how they would come back, if they would come back, for day two.” — Dawn Gross, MD PhD

Fortunately, the only phone calls the schools received were ones of gratitude in the interim saying thank you for being brave enough to teach this.

Teachers told us that students had raised conversations with them that they were aware of but had never spoken of publicly or in the depth that they were now doing. And they were grateful.

Part 3: Interactive Discussion

Along came day two. It was time students discover what matters most to them when it comes to life and death, and learn how to communicate it.

To do that, students played a game called Go Wish.

What became very clear as the students played this game was that they could talk about this. And even though it was in the context of imagining they were dying, what they realized was that it was actually about what mattered most to them right here, right now, while they were very much alive.

In exit surveys to see how it was to experience death ed, the vast majority of students said they were grateful they took it.

It turned out that talking about what matters most when it comes to life and death actually helps us uncover these things right now, while we’re very much alive, so we can live our life to the fullest until the very end.

This article is part original, part transcript of the 2017 End Well Symposium talk given by Jessica Nutik Zitter, MD, MPH, and Dawn Gross, MD PhD. You can view the full talk here.